One of my aims in life is to help people find words to describe what they’re experiencing and how they’re feeling. This blog post offers some, hopefully, useful words for those with pituitary conditions and their support networks along with some guidance on how to pronounce them for the trickier looking ones.

(Note on pronunciation – For the trickier words, I’ve broken them down into their various simpler sounds. You don’t pronounce the letters in brackets, they’re there to help you get the sound right. So, in the word inanition, below, where it says i(t) it’s telling you that you want the short ‘i’ sound from the word ‘it’.)

Inanition (Pronounced in-an- i(t)-shun): a lack of vigour, vitality, or enthusiasm due to a lack of nourishment be that social, physical, mental, or spiritual in nature. Inanition is a useful word to describe some of the limitations that living with a chronic health condition places on someone, as well as the impact of being a carer. If we take fatigue as an example (a commonly reported symptom of those with pituitary conditions as well as carers) it forces you to choose what you’re going to spend your energy on. People often report that they prioritise spending what little energy they have on work and home responsibilities, but this potentially leaves them with little or nothing left for socialising, hobbies or other meaningful activities and fun stuff thus leaving them starved of social contact, mental stimulation, and effective methods of relaxation and restoration. These various forms of starvation have an impact over and above the fatigue, and the ensuing lack of balance in our lives (you know what they say about all work and no play) leave people feeling flat with little or no enthusiasm and lacking interest in the world around them.

Immiseration (Pronounced (h)im-miz-err-ay-shun): defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as the act of making people (or a country or an organisation) poor. It’s unfortunately the case in this country that we no longer have a properly supportive welfare state. Coupled to which is an increasing tendency to blame people for getting ill and/or for not trying hard enough to get better. We’re all supposed to be dedicated to growing our country’s economy, but that isn’t matched by Government spending to improve life for the people who live here. Those with a pituitary condition aren’t to blame for getting their condition. It’s not uncommon for people with pituitary conditions to find that they need to change job because the long-term effects of their condition mean that they can no longer effectively do the job they were doing before, or they have to work reduced hours. Both of those can lead to reduction in income, and this can then mean having to move to a different part of town where the housing is less expensive. If you can’t afford to work then the current rates of financial support provided by the Government aren’t enough to enable even a basic standard of living, never mind a good quality of life. And since people with long-term conditions often incur extra expenses (such as paying for prescriptions, travelling to hospital appointments etc), having a chronic condition can very quickly push you into poverty. I like immiseration as a word because it acknowledges the misery that comes with not having enough resources to be able to live.

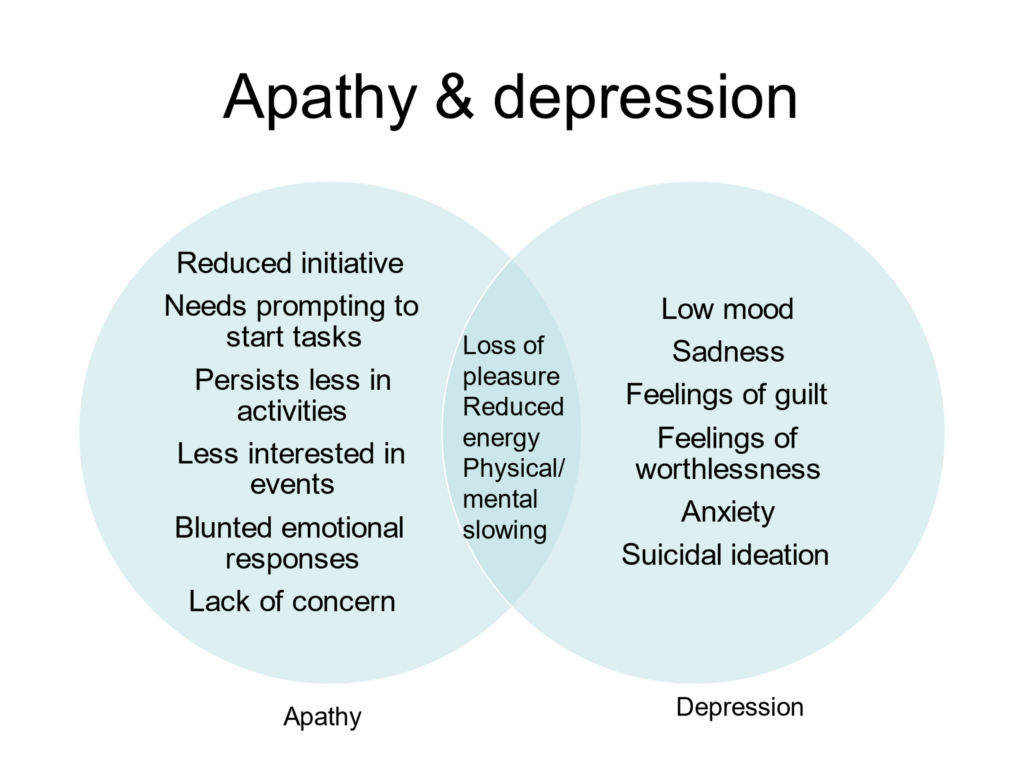

Apathy: a lack of interest, enthusiasm, or concern. You can have global apathy (i.e., no interest in anything at all, something that can be seen in people with some types of brain injury), or you can experience apathy in respect of one area of your life. For example, you might be so fed up at the way our politicians have been behaving, that you have no interest or enthusiasm for the upcoming elections. If you believe that your vote doesn’t count for anything, you might also think that it doesn’t really concern you either. There’s an interesting scientific paper from 2005 by Michael Weitzner, Steven Kanfer and Margaret Booth-Jones who described how their pituitary patients had apathy syndrome which they describe as a neurobiological illness, in other words, an illness caused by damage to the brain. Apathy is often misdiagnosed because its symptoms overlap considerably with those of depression (see drawing right). Based on anecdotal evidence, I’d say most people who describe a lack of interest, enthusiasm, or concern in respect to any or all aspects of their life are likely to be diagnosed with depression and offered anti-depressants.

Burnout: aphysical or mental collapse often caused by long term overwork or stress. It can also be described as the gradual erosion of a positive state of mind. Burnout is associated with an overwhelming feeling of emotional exhaustion of a sort that isn’t curable by resting. Burnt out people can often feel a sense of detachment, a feeling of dread or resentment at having to do things. Oddly to my mind, because it’s often caused by doing too much, it seems strange that burnout is often accompanied by a feeling of a lack of accomplishment. Burn out can lead to cognitive problems such as problems concentrating. I’ve included it here because it can occur in people with pituitary conditions who are valiantly trying to do all the things they would usually do in the face of their condition. It’s not a given that everyone with a pituitary condition faces problems in doing their usual activities, but some people are more affected by their condition than others. Our society these days puts great emphasis on the idea of working through or despite bouts of ill health. As a society we seem to be losing touch with the idea that resting is an important part of life, especially when we are not well. This societal pressure can cause people to push themselves to do things which can ultimately leave them so resource-depleted they burn out.

Ambiguous loss (pronounced: am-big-you-us): describes a loss that isn’t clear, usually the loss of a loved one. The person is alive, but they have changed so much that for themselves and for others they can seem like a different person. So, for example, a family member of someone with a pituitary condition might feel ambiguous loss if the person with the condition is different to how they used to be and it’s not clear if they’re ever going to return to how they were before the condition emerged. A person with a pituitary condition might experience ambiguous loss if they’re struggling to recognise themselves in how they’re respond to things. So, in essence, it’s something of a confusing state, where the person concerned is feeling that something is wrong, that a significant change has occurred, and it’s a change that leaves them feeling bereft in some way. Ambiguous loss goes to the heart of what it means to be human.

By Dr Sue Jackson

Sue is an Associate Lecturer at Plymouth University and an Independent chartered psychologist. She also works as a consultant for a variety of charities and pharmaceutical companies. Sue is a science writer and researcher working on a variety of projects round the UK.