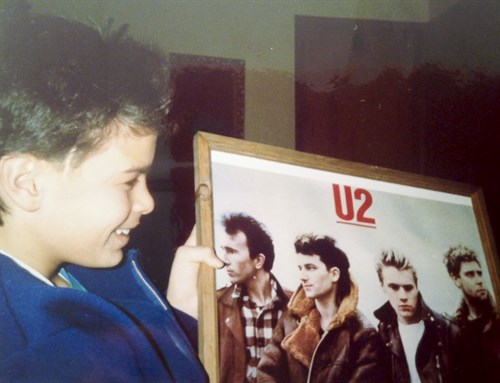

In 1984, as I entered Rome Free Academy high school in my hometown of Rome, New York, the feeling that I was different from other kids started to intensify.

While the other boys and girls had added height and progressed through puberty in junior high, I had remained unchanged—a fifteen-year-old boy standing four-feet-eight-inches tall and weighing eighty pounds, with soft, round, feminine features. I had no summer growth spurt. No sprouting of coarse fibers on the upper lip or pubic or underarm hair. My high-pitched voice did not deepen. The gap between me and the other kids widened, and I felt stuck on a deserted highway while they were whizzing past me in fast cars, looking back at me in the rearview mirror.

~~~~~~~

After pestering my parents about my stunted growth, my family physician in Rome referred me for an appointment with an endocrinologist at SUNY Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse (now called Upstate University Hospital.)

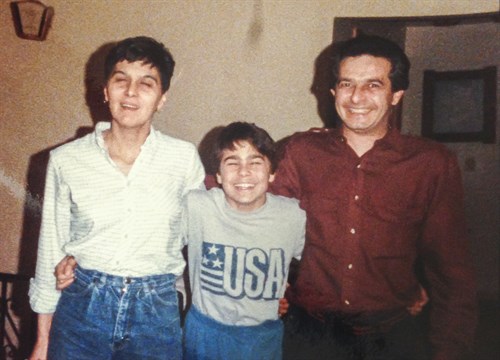

My parents had been separated for a couple of years, but they tried to keep things civil, and that included my father attending family functions, school events, and doctors’ appointments.

After we arrived at the hospital, we checked in at the main desk at the Pediatric Endocrine Center and then were escorted to an exam room.

Kelsey, the nurse practitioner for the center’s director, Dr. Friedman (name changed), came in and introduced herself to my parents and me. She was short with brown hair and she wore a white coat and carried a clipboard. She took a seat, sliding her chair closer to the table, and she started asking me questions in order to get a full medical history.

She asked me about my school, recreational activities, and diet – focusing on exact portions and the time of day I ate my meals and snacks. She asked questions about my sleeping pattern, whether I had grown out of my clothes or needed new shoes within the last year, my use of deodorant, and whether I was typically hot or cold. She was thorough in her questioning and it seemed apparent she sought to find the cause of why my growth had stopped.

Some time later Dr. Friedman entered the room, followed close behind by a phalanx of interns and residents. My mother liked him right away, as he exuded an air of aplomb—a medical professional in complete control; I disliked him based on an arrogance I perceived he possessed.

He checked my reflexes and instructed me to bend over at the waist, touching my spine as I stood up; he felt around my throat and glands and held his cold stethoscope to my back and listened to my breath sounds. He had me raise my arms and felt around my armpits, telling the interns I had sparse axillary hair (underarm hair).

Dr. Friedman turned off the overhead fluorescent lights, directed me to look against a far wall, and shined a bright pinpoint of light directly into my eyes, as he peered at the optic nerve.

Then he had me lie down on the exam table. He pulled up my gown and pressed his hands into my abdomen and felt around my organs.

Next he measured the size of my gonads using some yellow plastic eggs chained together, pointing out to the interns that I had hypogonadism—marked by small testicles and scant pubic hair.

He stepped away from the exam table and stood in front of me. He questioned me about my eating habits, reviewing the information the nurse practitioner had written down. I think he asked me why I was skipping breakfast and eating only a light lunch at school. My mother didn’t let me answer; she told him I was obsessed with diet and that I had been restricting calories. “He loves ice cream, but he won’t eat it because he’s afraid of gaining weight,” she said. I think in her mind she was being a dutiful mother by sharing the private information.

I sat with my head down, half naked and exposed on the exam table. Of course I was afraid of packing on weight. I was in tenth grade and I looked like I was twelve years old. And while I knew I couldn’t initiate a vertical growth spurt, I decided I could at least try to prevent a horizontal spread that would make my body asymmetrical.

But I did not explain this to Dr. Friedman, and he chided me for my dietary restrictions, telling my mother, “Well he won’t grow if he doesn’t eat.” He said something to me like, “You understand that, right?” I nodded my head, and he said, “My kids are teenagers and you can’t stop them from eating.”

After leaving the room to consult with his team, Dr. Friedman returned and held up a graph displaying the caloric needs of teenage boys. He also showed my parents my growth chart, which revealed how my progress had stalled in recent years.

He then gave me a prescription to spur growth: he told me to eat a balanced breakfast, lunch, and dinner every day and add one Carnation instant breakfast drink in the morning and another one at night before bed.

I felt like he had wasted our time. This was not the answer I had sought; this changed nothing. I wanted a medical explanation for my delayed puberty, not a food supplement.

But I don’t blame Dr. Friedman, as he followed the evidence presented. Still, I think he considered me only as a patient reflecting numerical data—a point on growth chart, nothing more. And while I didn’t believe the addition of Carnation drinks would alter my height, I pretended to accept Friedman’s instructions. I said I understood the importance of eating enough and I agreed to follow the regimen outlined by the doctor.

Before we left his clinic, Dr. Friedman had ordered a lateral head CT and an X-ray of my left hand and wrist to determine the discrepancy between my biological age and my chronological age; the goal was to estimate my bone age and make an adult height prediction. The outcome: my chronological age was fifteen and two months and the X-ray showed my bone age was approximately thirteen years old.

The scan of my head revealed a cloudy mass in the sella region at the base of the skull, and the results of a follow-up CT scan with radiation contrast came a few weeks later. I received the news of the brain tumor diagnosis from Dad, after he picked me up from wrestling practice on a cold November night.

~~~~~~

Our wrestling team was primed to compete in our first match in a few days, and Coach Sanderson (name changed) had us conclude practice by running up and down the stairs inside the school; afterwards, we marched through the hallways and entered the nurse’s office to weigh in.

I was set to wrestle at the JV level (and a possible long shot for varsity) in the eighty-eight or ninety-one-pound class.

After weighing in on the night I found out about the tumor, I put on my black pea coat, pulled down a knit hat around my ears, slung my book bag over my shoulders, and walked out the back door of the gym to meet my father, who had parked in the lot behind the high school.

The cold air hit my face and stung my gloveless hands as I strode toward the car; a floodlight cast a large net of bright, white light on the pavement. Dad drove up and I got in.

He put the car in park and let it idle, and as I slid into the seat and adjusted myself, he leaned over and kissed me on the cheek, his tan winter coat brushing against the steering wheel. I felt a trace of his razor stubble against my skin and I could smell a faint odor of Aqua Velva or Brut, combined with cigarette smoke. The heater hummed and he lowered the blast of air and turned and looked at me. I wondered why we weren’t moving yet. He wasn’t crying, but he appeared on the verge of spilling emotions.

“What’s the matter Dad?” I asked.

“Upstate called your mother today,” he said. He switched on the overhead light, reached into his jacket pocket, and pulled out a torn piece of paper. “Here,” he said, handing me the slip of paper, “this is what they think you have. I wrote it down, but I don’t know if I spelled it right.”

Scribbled in faint blue ink was the word “craniopharyngioma,” although my father had misspelled it. His voice cracked a bit as he said, “It’s cranio-phah-reng … something like that … I don’t know, it’s some kind of brain tumor.”

I looked at the paper and felt a wave of satisfaction as my father let out a sigh. He shook his head and said, “I prayed to God that this wouldn’t happen to you, when you were born, that you wouldn’t have to go through the same thing I did.” His words referred to his own health crisis as a teenager—one that caused small stature and delayed puberty and led to ridicule by his classmates.

He had been born with a hole in his heart, a ventricular septal defect. On June 12, 1959, when my dad was sixteen years old, pioneering cardiac surgeon C. Walton Lillehei performed open-heart surgery on him at the University of Minnesota Hospital, successfully repairing the defect. The heart problem interrupted Dad’s high school years and he faced a long recovery; but he rebounded after the surgery, lifting weights to add strength and put on muscle. He graduated high school from St. Aloysius Academy in Rome, went to work at the city’s Sears Roebuck store, and eventually grew to a height of about five-feet-five-inches tall.

On this night, after sharing the news with me, he seemed locked into position in the driver’s seat, unable to shake off the news and go through the motions of putting the car in gear and driving away. I think we may have clutched hands, and I said, “It’s OK Dad. Don’t worry. But what do we do now? What’s next?”

“You have to go back there for more tests. You may need surgery.”

“All right,” I said, “it’s OK.”

He switched off the overhead light and pulled out of the parking lot. We grew silent inside the car as we passed the naked trees lining Pine Street. We crossed the intersection at James Street and made our way toward Black River Boulevard.

While my father was crestfallen, I remember being elated as I sat in the passenger seat. The CT scan with contrast had given me a medical diagnosis—a reason for my growth failure; it explained why my body had not changed and why I was so different from the other boys my age. I still considered myself a physical anomaly, but the tumor proved it wasn’t my fault.

That knowledge gave me some satisfaction, and I couldn’t help feeling a stirring of excitement. I looked down at the piece of paper again and studied the word—“craniopharyngioma.” I tried to sound it out in my head while my dad drove on, and I thought the word would roll off my tongue like poetry if I said it out loud. Craniopharyngioma. Cranio-Phar-Ryng-Eee-Oh-Mah … sort of like onomatopoeia.