Cihan Atila, MD,Departments of Endocrinology, Diabetology and Metabolism, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland

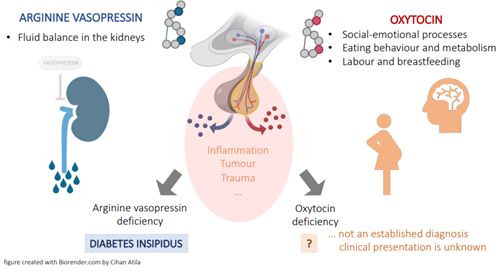

The posterior lobe of the pituitary gland stores the two hormones, oxytocin and arginine vasopressin (AP). Both are released into the blood circulation and directly into the brain, regulating various physiological processes in the body. Disruptions of the pituitary gland and, thus, damage to the hormone-producing neurons (e.g., due to inflammation, head injury, or tumour) can cause a deficiency of these hormones.

Arginine vasopressin acts mainly in the kidneys and regulates the fluid balance by concentrating urine. An arginine vasopressin deficiency, formally known as central diabetes insipidus, is a rare disease affecting one in 25,000 individuals and characterised by excessive urination (>50 ml urine per kg body weight in 24 h) and compensated by excessive drinking (>3 litres fluid per day). Arginine vasopressin deficiency (central diabetes insipidus) is an established disorder, and patients can be treated effectively with desmopressin, a synthetic medication mimicking the effect of arginine vasopressin in the kidneys.

Oxytocin has many well-known effects, including its involvement in labour and breastfeeding, regulation of social and emotional processes in the brain, and its impact on eating behaviour and metabolic effects. Oxytocin deficiency, on the other hand, is not an established disorder, and the clinical symptoms in patients with a potential deficiency are poorly studied. One of the reasons why oxytocin deficiency has not yet been established as a disorder may be that no diagnostic tests are available to identify such a deficiency.

Labour and breastfeeding

Oxytocin is involved in the regulation of labour by stimulating cervical dilatation and facilitating the contraction of the uterus (womb). In addition, oxytocin also stimulates the milk let‐down in breastfeeding women. Therefore, oxytocin (administered as an intravenous infusion or nasal spray) can be applied to women with weak contractions during labour and those with breastfeeding difficulties after giving birth to a child. Given the functions of oxytocin, patients with known pituitary conditions could develop prolonged labour and breastfeeding difficulties. In a study with four patients with a known arginine vasopressin deficiency, delivery took place either through a cesarean section or through vaginal delivery that required labour induction as well as oxytocin administration for augmentation, pointing to a likely deficit of oxytocin. However, there are also some cases of a known arginine vasopressin deficiency (central diabetes insipidus) with normal labour and without requiring oxytocin, suggesting that oxytocin from the pituitary may not be mandatory for labour or at least only play a partial role.

Social and emotional processes

Brain regions that play an important role in social-emotional behaviour show a high density of oxytocin receptors expression. Oxytocin promotes social effects such as in-group favouritism and protection against social threats, interpersonal trust and attachment, increases empathy, and is involved in the emotion recognition of others. Furthermore, oxytocin buffers responses to social stress, reduces cortisol (stress hormone) levels during conflict situations, improves self-representations in patients with anxiety disorder, and reduces amygdala response to emotional stimuli reducing fear and anxiety.

In animal studies, mice with a deficit in oxytocin show an impairment in forming social memories and demonstrate higher anxiety-related behaviours. These results were substantiated by the fact that the administration of oxytocin rescued oxytocin deficit mice from these observations.

Only limited research has been devoted to the role of oxytocin in patients with hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction and focused primarily on patients with craniopharyngioma, assuming direct tumour-induced or surgical damage to oxytocin-producing neurons. Data demonstrates personality changes and increased psycho-social comorbidities – including anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal. This was confirmed by a systematic review showing behavioural dysfunctions in 57%, and social impairment and difficulties holding relationships in 40%. Interestingly, the age of onset appears to influence the type of social-behavioural dysfunction. While adult-onset had higher levels of anxiety and depression, younger patients had more impact in the domains of social isolation. Research in patients with confirmed posterior pituitary dysfunction (with a known arginine vasopressin deficiency – central diabetes insipidus) demonstrated higher depression and anxiety levels, self-reported autistic traits, lower joy when socialising, and worse scores on an emotional recognition task than healthy adults. To date, only one small study and one case report, i.e., in ten patients with arginine vasopressin deficiency (central diabetes insipidus) due to craniopharyngioma, demonstrated an improvement in the ability to identify others’ emotions after a single dose of oxytocin.

Eating behaviour and metabolism

The brain’s regulation of food intake and appetite is complex and involves many different hormones and neuronal connections. Recently, the role of oxytocin in regulating food intake and metabolism has become appreciated. In animal studies, mice with a deficit in oxytocin have poor blood sugar control, gain weight, and develop obesity. Interestingly, the administration of oxytocin reduced food intake in these animals and improved blood sugar control. In humans, the same effects can be observed, and oxytocin (given as a nasal spray) reduces food intake at meals, snack food consumption, reward-induced eating, and obesity. Given the potential risk for an oxytocin deficiency in patients with hypothalamic-pituitary diseases, especially those with a confirmed arginine vasopressin deficiency (central diabetes insipidus), one could assume that these patients would develop changes in eating behaviour and have poor metabolic implications after the onset of the disease. One case report was published about a 13-year-old boy with a craniopharyngioma and surgical damage to the neurons producing arginine vasopressin (due to the proximity to oxytocin-producing neurons, also assuming an oxytocin deficiency) who developed changes in eating behaviour and obesity. This type of obesity is often referred to as “hypothalamic obesity”. It is considered a serious morbidity that often contributes to the poor quality of life in these patients with only a few treatment options. In this boy, a 48-week administration of oxytocin improved satiety (leaving food unfinished), decreased urgency to eat (tolerating longer intervals between snacks and meals), and overall decreased food preoccupation, consequently leading to weight reduction. However, it should be mentioned that such a metabolic change is less often observed in patients with DI that develops from another cause.

Patients with known pituitary disease, especially those with a known arginine vasopressin deficiency (central diabetes insipidus), are at high risk for an additional oxytocin deficiency. Future research needs to develop new diagnostic tests to prove such a deficiency. In addition, studies need to investigate how oxytocin deficiency is clinically characterised and whether daily administration of oxytocin could improve of symptoms (e.g. quality of life and psychological symptoms, metabolic changes).